Nothing like being paid to read a book — a win-win situation for me.

Here’s a link to my review in the Sunday Express newspaper of a new history of MI6, called “The Art of Betrayal” by Gordon Corera, the BBC’s Security Correspondent.

And here’s the article:

REVIEW: THE ART OF BETRAYAL — LIFE AND DEATH IN THE BRITISH SECRET SERVICE

Friday August 19, 2011

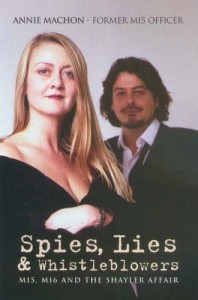

By Annie Machon

THE Art of Betrayal: Life and Death in the British Secret Service

Gordon Corera Weidenfeld & Nicholson, £20

THE INTRODUCTION to The Art Of Betrayal, Gordon Corera’s unofficial post-war history of MI6, raises questions about the modern relevance and ethical framework of our spies. It also provides an antidote to recent official books celebrating the centenaries of MI5 and MI6.

Corera, the BBC’s security correspondent, has enjoyed privileged access to key spy players from the past few decades and, writing in an engaging, easy style, he picks up the story of MI6 at the point where the “official” history grinds to a halt after the Second World War.

Spy geeks will enjoy the swashbuckling stories from the Cold War years and he offers an intelligent exploration of the mentality of betrayal between the West and the former Soviet Union, focusing on the notorious Philby, Penkovsky and Gordievsky cases among many others.

For the more cynical reader, this book presents some problems. Where Corera discusses the aimless years of MI6 post-Cold War attempts at reinvention, followed by the muscular, morally ambiguous post‑9/11 world, he references quotes from former top spies and official inquiries only, all of which need to be read with a healthy degree of skepticism. To use a memorable quote from the Sixties Profumo Scandal, also mentioned in the book: “Well, they would say that, wouldn’t they?”

In Corera’s view, there has always been inherent tension in MI6 between the “doers” (who believe that intelligence is there to be acted upon James Bond-style and who want to get their hands dirty with covert operations) and the “thinkers” (those who believe, à la George Smiley, that knowledge is power and should be used behind the scenes to inform official government policy).

He demonstrates that the “doers” have often been in control and the image of MI6 staffed by gung-ho, James Bond wannabes is certainly a stereotype I recognise from my years working as an intelligence officer for the sister spy organisation, MI5.

The problem, as this book reveals, is that when the action men have the cultural ascendancy within MI6 events often go badly wrong through establishment complacency, betrayal or mere enthusiastic amateurism.

That said, the opposing culture of the “thinkers”, or patient intelligence gatherers, led in the Sixties and Seventies to introspection, mole-hunting paranoia and sclerosis.

Worryingly, many former officers down the years are quoted as saying that they hoped there was a “real” spy organisation behind the apparently amateur outfit they had joined, a sentiment shared by most of my intake in the Nineties.

Nor does it appear that lessons were learned from history: the Operation Gladio débâcle in Albania and the toppling of Iran’s first democratically-elected President Mossadeq in the Fifties could have provided valuable lessons for MI6 in its work in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya over the past two decades.

Corera is remarkably coy about Libya despite the wealth of now publicly-available information about MI6’s meddling in the Lockerbie case, the illegal assassination plot against Gaddafiin 1996 and the dirty, MI6-brokered oil deals of the past decade.

Corera pulls together his recurring themes in the final chapters, exploring the compromise of intelligence in justifying the Iraq war, describing how the “doers” pumped unverified intelligence from unproven agents directly into the veins of Whitehall and Washington.

Many civil servants and middle-ranking spies questioned and doubted but were told to shut up and follow orders. The results are all-too tragically well known.

Corera does not, however, go far enough.

He appreciates that the global reach of MI6 maintains Britain’s place in an exclusive club of world powers. At what price, though?

Here is the question he should perhaps have asked: in light of all the mistakes, betrayals, liberties compromised, lessons unlearned and deaths, has MI6 outlived its usefulness?

Annie Machon is a former MI5 intelligence officer and author.

Verdict 4/5