Irish Sunday Tribune, July 2005

What really went on in the secret service?

Suzanne Breen

‘THEY’RE probably out there now, walking about, looking for targets, ” says former spy, Annie Machon, as she surveys the bustling bars, restaurants and shops in Gatwick Airport. MI5 used Heathrow and Gatwick in training courses. Officers would be sent to the airports and instructed to come back with one person’s name, address, date of birth, occupation and passport or driving licence number … the basic information for MI5 to open a personal file.

“They’d have to go up to a complete stranger and start chatting to them. One male officer nearly got arrested. It was much easier for women officers … nobody’s suspicious of a woman asking questions.”

Tall, blonde and strikingly elegant, Machon (37) could have stepped out of a TV spy drama. She arrives in a simple black dress, with pearl earrings, and perfect oyster nails. She is charmingly polite but, no matter how many questions you ask, she retains the slightly detached, inscrutable air that probably made her good at her job.

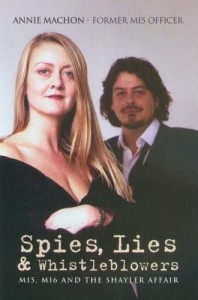

A Cambridge Classics graduate, her book, <em>Spies, Lies and Whistleblowers</em>, has just been published. She worked in ‘F’ branch … MI5’s counter-subversion section … and ‘T’ branch, where she had a roving brief on Irish terrorism. MI5 took 15 months to vet the book. Sections have been blacked out. If Machon discloses further information without approval, she could face prosecution under the Official Secrets Act.

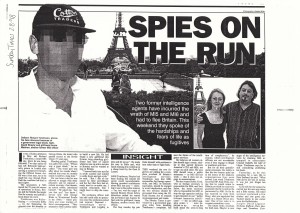

She left MI5 deeply disillusioned. In 1997, she went on the run from the UK with her boyfriend, former fellow spy David Shayler (39). He was subsequently jailed for disclosing secrets, including that MI6 had allegedly funded a plot to assassinate Colonel Gaddafi.

Machon had “responsibility and freedom” in MI5 when combating Irish terrorism. “It was wonderful when you got results, when you stopped a bomb. That was why I’d joined. There was a huge understanding of the IRA and the Northern Ireland conflict. We weren’t just a bunch of bigots saying “string up the terrorists”. Some managers might have had that attitude but it wasn’t shared by most officers. They acknowledged the IRA as the most professional terrorist organisation they’d dealt with. Loyalists, and republican splinter groups like the INLA, were a lot less sophisticated.”

Machon didn’t witness state collusion but is “watching with interest” as cases unfold. She voices some ethical concerns: MI5 ran a Garda officer as an undeclared agent, which was illegal in the Republic. If it wanted to tap a phone in the Republic, no warrant was needed and there was no oversight procedure. An MI5 officer simply asked GCHQ, which intercepts communication, to set it up.

MI5’s approach to the law led to bizarre situations:

“Officers covertly entered a house in Northern Ireland to install bugging equipment. They trashed it up and stole things to make it look like a burglary. But MI5 lawyers said it wasn’t legally acceptable to steal so the officers had to go and put the goods back which made it look even more suspicious.”

Machon attended security meetings in Northern Ireland. Her life was never in danger, she says. The only colleagues she knew who were killed were on the Chinook helicopter which crashed off the Mull of Kintyre in 1994.

Machon had joined the intelligence services three years earlier. She worked from an office in Bolton Street, Mayfair, one of MI5’s three buildings in London. “It was very dilapidated. There were ancient phones, with wires crossing the floor stuck down with tape. It had battered wooden desks and threadbare carpets. There were awful lime-green walls. The dress code in MI5 was very Marks and Spencer. MI6 (which combats terrorism abroad) was much smarter, more Saville Row.”

MI5’s presence in the building was meant to be a secret but everybody knew, says Machon: “The guide on the open-top London tour bus which passed by would tell passengers, ‘and on your right is MI5’. We were advised to get out of taxis at the top of the street, not the front door, but all the drivers knew anyway. Later, we moved to modern headquarters in Thames House.”

Being a spy isn’t what people think, Machon says. “It wasn’t exactly James Bond, with glamorous, cocktail-drinking espionage. There were exciting bits, like meeting agents in safe houses, but there were plenty of boring days. Mostly, I’d be processing ‘linen’ — the product from telephone taps … or reading intercepted mail or agents’ reports. You get to know your targets well from eavesdropping on their lives. You learn all sorts of things, like if they’re sleeping with someone behind their partner’s back. It’s surreal knowing so much about people you don’t know; and then it rapidly becomes very normal.”

Machon claims the intelligence services were often shambolic, and blunders meant three IRA bombs in 1993 … including Bishopsgate, which cost £350m …could have been prevented. “MI5 has this super-slick image but sometimes it was just a very British muddle. Tapes from telephone taps would be binned without being transcribed because there wasn’t the personnel to listen to them. On occasions, MI5 did respond quickly, but then it could take weeks to get a warrant for a phone tap because managers pondered so long over the application wording … whether to use ‘but’ or ‘however’, ‘may’ or ‘might’.

Machon claims the intelligence services were often shambolic, and blunders meant three IRA bombs in 1993 … including Bishopsgate, which cost £350m …could have been prevented. “MI5 has this super-slick image but sometimes it was just a very British muddle. Tapes from telephone taps would be binned without being transcribed because there wasn’t the personnel to listen to them. On occasions, MI5 did respond quickly, but then it could take weeks to get a warrant for a phone tap because managers pondered so long over the application wording … whether to use ‘but’ or ‘however’, ‘may’ or ‘might’.

“Mobile surveillance (who follow targets) were bloody good. There were some amazingly capable officers who were often wasted. Despite everything promised about MI5 modernising, it remained very hierarchical, with the old guard, which had cut its teeth in the Cold War, dominating. They were used to a static target. They’re not up to the job of dealing with mobile extremist Islamic terrorism. We’ve been playing catch-up with al Qaeda for years.”

Machon says MI5 pays surprisingly badly: “I started on £15,000 … entrants now get about £20,000. A detective constable in the Met was on twice my salary. Of course, it’s about more than money but you must reward to keep good people. If you pay peanuts, you end up with monkeys.”

Machon grew up in Guernsey, in the Channel Islands, the daughter of a newspaper editor. “I was apolitical. My only knowledge of spying was watching John Le Carre’s drama Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.” After taking Foreign Office exams, she received a letter on MoD notepaper. “There may be other jobs you would find more interesting, ” it said. Intrigued, she rang. It was MI5.

During the recruitment process, every aspect of her life from the age of 12 was investigated. “I’d to nominate four friends from different phases of my life. After they were questioned, they had to nominate another four people. I confessed to smoking dope twice. I was quizzed about my sexual history by a sweet old lady who looked like my grandmother but resembled Miss Marple in her interrogation. She asked if I was gay. The rules have since changed, but then MI5 regarded homosexuality as a defect. If you lied and were found out, you’d be sacked on the spot. In theory, they regarded promiscuity as a weakness, but there were plenty of extra-marital affairs. One couple were twice caught shagging in the office. The male officer, who was very bad at his job, was put on ‘gardening leave’ … sent home on full pay. The woman, an Arabic-speaking translator who was great at her job, was sacked.”

A culture of “rampant drunkenness” existed, says Machon: “There was an operation against a Czech diplomat who was also a spy. The officer running it got pissed, went round with his mates to the diplomat’s house, and shouted operational details through the letter-box at him.”

Recruits were encouraged to tell family and close friends they were MI5, and anyone else that they worked for the MoD.

MI5 had one million personal files (PFs), Machon says. “I came across files on celebrities, prominent politicians, lawyers, and journalists. It was ridiculous. There were files on Jack Straw, Mo Mowlam, Peter Hain, Patricia Hewitt, Ted Heath, Tony and Cherie Blair, Gareth Peirce, and Mohamed Al Fayed. There was a file on ‘subversives’ in the music industry, including the Sex Pistols and UB40.

MI5 had one million personal files (PFs), Machon says. “I came across files on celebrities, prominent politicians, lawyers, and journalists. It was ridiculous. There were files on Jack Straw, Mo Mowlam, Peter Hain, Patricia Hewitt, Ted Heath, Tony and Cherie Blair, Gareth Peirce, and Mohamed Al Fayed. There was a file on ‘subversives’ in the music industry, including the Sex Pistols and UB40.

At recruitment, I was told MI5 no longer obsessed about ‘reds under the bed’, yet there was a file on a schoolboy who had written to the Communist Party asking for information for a school project. A man divorcing his wife had written to MI5 saying she was a communist, so a file was opened on her. MI5 never destroys a file.”

The ranking in importance of targets could be surprising. PF3 was (and is) Leon Trotsky; PF2, Vladimir Ilych Lenin; PF1 was Eamon De Valera.

MI5 currently has around 3,000 employees. About a quarter are officers; the rest are technical, administrative and other support staff, according to Machon.

In recent years, MI5 appointed two female director generals … Stella Rimmington, and the current director general, Dame Eliza Manningham-Butler. “I always found Stella very cold and I wasn’t impressed with her capabilities. There was an element of tokenism in her appointment. Eliza is like Ann Widdecombe’s bossy sister, ” says Machon, mischievously raising an eyebrow. “She scares a lot of men. She is seen as hand-bagging her way to the top.”

Machon says the only way of responding to the growing terrorist threat is for the present intelligence infrastructure to be replaced by a single counter-terrorist agency. The intense rivalry between MI5, MI6, Special Branch and military intelligence means they’re often more hostile to each other than to their targets. ID cards and further draconian security legislation will offer no protection, she says.

Machon was active in the anti-war campaign. She believes there is an “80% chance” that Dr David Kelly, the government scientist who questioned the claim that Iraq could launch weapons of mass destruction within 45 minutes, didn’t commit suicide but was murdered on MI5’s instructions.

Other suspicious minds wonder if Machon and Shayler ever left MI5. Could it be an elaborate plot to make them more effective agents? By posing as whistleblowers, they gain the entry to radical, leftwing circles.

Machon dismisses this theory: “It would be very deep cover indeed to go to those lengths. Gareth Peirce is our solicitor. She trusts us and she’s no fool.” Machon says while they have no regrets, they’ve paid a huge emotional and financial price for challenging the secret state. They survive on money from the odd newspaper article and TV interview. Home is a small terraced house in Eastbourne, east Sussex, where they grow tomatoes and have two cats.

Are they still friends with serving MI5 officers? “No comment!” says Machon with a smile. These days, she goes places she never did.

When she addresses leftwing meetings, someone often approaches at the end. “You must know my file?” they say.

‘Spies, Lies & Whistleblowers’ by Annie Machon is published by The Book Guild, £17.95

They wanted a fairly classic talk from me — the whistleblowing years, the lessons learnt and current political implications, but also what we can to do fight back, so I called my talk “The Panopticon: Resistance is Not Futile”, with a nod to my sci-fi fandom.

They wanted a fairly classic talk from me — the whistleblowing years, the lessons learnt and current political implications, but also what we can to do fight back, so I called my talk “The Panopticon: Resistance is Not Futile”, with a nod to my sci-fi fandom.

The

The