Stuart Jeffries of The Guardian interviewed me in November 2002:

The Spy who Loved Me

Annie Machon quit her job at MI5 and endured three years on the run — all for the sake of her partner David Shayler, who was jailed last week. She tells Stuart Jeffries why.

Annie Machon fell in love with a spy codenamed G9A/1. It was 1991 and she had been working in MI5’s counter-subversives section for two months. “The first thing I noticed about him is that he’s leonine,” she says over lunch. “I think he’s drop-dead gorgeous. We’d be in section meetings which we’d get dragged to occasionally and told what to think. He stood out because he asked the awkward questions. He was very clear-cut and challenging.”

G9A/1 was David Shayler, the renegade British spy who last week was sentenced to six months for breaking the Official Secrets Act after leaking secret documents to the press. He’s the one regularly branded as a fat, sweaty, boozy, big-mouthed traitor. The kind of upstart who might take his martini stirred rather than shaken. “Yes, that’s what they say, isn’t it?” says Machon, as she lights another cigarette. She exhales. “He’s nothing like that. Everybody loves to portray him as this slob from the north-east. But he’s not only a whistleblower trying to do something honourable. He’s also really intelligent. I love him, and am very proud of him for what he did.”

Some people think you’re the brains behind Shayler. “That’s not true. When I started at MI5, I went in as GD5. GD stands for general duties. It’s very gradist. Dave went in as GD4, which meant that they were fast tracking him. They thought he was really sharp. And they were right. In fact, he’s very sparky and great company. We just clicked, basically.” How did MI5 bosses feel about office romances? “They encouraged them. They regarded those sorts of relationships as politically expedient, and operationally quite sensible. There were quite a few couples at MI5.”

How did Annie Machon, a classics graduate from Girton College, Cambridge, get recruited as a spook in the first place? A nudge in the quad, a glass of sherry with a shifty don? “No, I had sat the exam to be a diplomat. Then I got a letter.” She was impressed by the 10-month recruitment process. “It was very thorough with lots of tests and background checks. It seemed like a professional organisation. We were supposed to be part of the new generation. People from different backgrounds and different experiences were supposed to be brought in — people who could think on their feet and think laterally. We both joined thinking it sounded good for the country, which sounds quite idealistic now.”

When did scepticism set in? “Very quickly.” Machon and Shayler were employed to look for reds under the bed, but they couldn’t find any, even though they studied the file on that dangerous leftwing subversive Peter Mandelson ever so assiduously. “We were basically trying to track down old communists, Trotskyists and fascists, which to us seemed like a waste of time. The Berlin Wall had come down several years before. We were both horrified that during the 1992 election we were summarising files on anybody who stood for parliament. We were also horrified by the scale of the investigations. We both argued most vociferously that we shouldn’t be doing this.”

After two years, both Machon and Shayler were moved to T‑branch, where they worked on countering Irish terrorist threats on the mainland. “We were both doing well. We were good operatives and they wanted the best in that section. I don’t want to be egotistical but that was the truth.”

The pair hoped that this relatively new section would operate better. “There were several young and talented agents who did their best. But because of management cock-ups they couldn’t do their jobs properly and peoples’ lives were lost.” What was the problem? “They had all these old managers who had been there for donkey’s years. They were caught in the wrong era — instead of dealing with static targets, they had a mobile threat in the IRA and they just couldn’t hack it. It was a nightmare, especially because there were so many agencies involved — MI5, Special Branch, the RUC, GCHQ. They all had their own interests. That was why Bishopsgate happened.” Shayler later claimed that MI5 could have stopped the 1993 IRA bombing of Bishopsgate in the City of London, which left one dead and 44 injured.

Why didn’t you leave then? “It was very easy to get into a stasis. You have lots of friends there. But when you get to a more established section like the Middle East terrorism section and you see it’s the same, then you think about quitting.”

In 1995, Shayler discovered that MI6 had paid an agent who was involved in the plot to assassinate the Libyan leader, Muammar Gadafy. Why was that wrong? “Apart from the immorality of it, the general consensus from the intelligence community was that the assassination of a well-established head of state by an Islamic fundamentalist in a very volatile area was not a good idea. It was crazy, but these bozos at MI6 wanted to have a crack at him.”

Then there was the case in which MI5 tapped a journalist’s phone. “For us, that’s what broke the camel’s back. A tap was only to be used in extremis, and this was nothing like that.”

Why didn’t you go quietly? “Well, other officers did. In the year we left, 14 officers resigned. The average figure was usually four. It was very scary. Dave is someone who thinks he should fight for what he believes in. And I knew what he was talking about. I knew he had to have the support against the massed forces of darkness. When you work there, the only person you can report something to is the head of MI5 but if you’re complaining about alleged crimes on behalf of MI5, they’re not going to allow you to do that, so you’re in a Catch 22 situation.”

In August 1997, Shayler sold his story to the Mail on Sunday. The day before publication the couple fled to Utrecht in Holland. “We left before the piece came out because they would have knocked down our doors and arrested Dave. I felt terrified. But we managed to stay one step ahead.” Why was he the whistlebower rather than you? “He had more access to what was going on — he was right in the middle of the Gadafy plot — and felt very strongly about it.”

The couple ended up in a French farmhouse. “It was in the middle of nowhere. No TV, no car. For 10 months we spent every day together. He would write his novel during the day.” What were you doing? “I was keeping house. We enjoyed each other’s company.” No rows? “Plenty.”

The couple tried to negotiate to return to Britain without Shayler being prosecuted, but with an undertaking that his allegations be officially investigated. “We got a complete lack of interest.” Then, during a stay in Paris, Shayler was arrested in a hotel lobby. “We’d just been watching Middlesbrough on TV. They lost, of course. Then I didn’t see him for two months.” He spent nearly four months in La Santé, Paris’s top-security prison which also houses Carlos the Jackal who used to yell “David English!” to the renegade spy from his cell. “I was bereft.” How are you going to deal with his current imprisonment? “I’ll just deal with it. It’s horrible, but I’m tough.”

A French judge ruled the extradition demand was politically motivated and released him. The couple then rented a flat in Paris and holed up for a year. “As far as the British authorities were concerned, we could rot. They didn’t want us to come back. We made a little money from journalism, but this wasn’t the life we wanted.” Why in August 2000 did the spies decide to come home? “We had managed to negotiate a return without risking months of remand. Dave thought he would be able to present his case to peers: yes, he did take £40,000 from the Mail on Sunday but that isn’t why he told the story. He never got the chance. In the trial they tied his hands behind his back. He couldn’t say anything to the jury. The reporting restrictions were extraordinary.”

She visited Shayler in jail for the first time on Tuesday. How was he? “He’ll be all right.” Now what? “I wait. And in the meantime, we get our legal case together. We’re going to Europe, British justice is useless.”

Wouldn’t you like to put all this behind you and get on with your lives. “We will. But not yet. It could take five years to clear his name.” Machon, poised and clad in black, turns a cigarette in her fingers. “You know, when I started this case I was in my 20s. Now I’m 34. I don’t think I’ll have finished with it until I’m in my 40s. I wish I’d never got involved with MI5. I wouldn’t touch them with a bargepole if I had my time again.” I leave Machon alone at a café table writing a letter to the man no longer codenamed G9A/1.

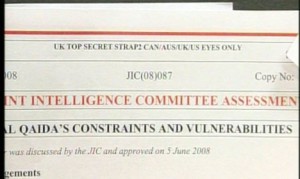

In this case, it appears that the official may not even have had permission to remove these documents in the first place. Cabinet Minister, Ed Miliband, is quoted in the Daily Mail today as saying that there had been ‘a clear breach’ of rules forbidding the removal of documents without authorisation. Then, having removed these documents illegally, the intelligence official appears to have taken them out of the security briefcase and read them in public, before leaving them on the train.

In this case, it appears that the official may not even have had permission to remove these documents in the first place. Cabinet Minister, Ed Miliband, is quoted in the Daily Mail today as saying that there had been ‘a clear breach’ of rules forbidding the removal of documents without authorisation. Then, having removed these documents illegally, the intelligence official appears to have taken them out of the security briefcase and read them in public, before leaving them on the train.